There I was last night, nice and comfortable watching another epic Ken Burns production on Public Television, this time on The Dust Bowl in the Southern Plains. Ken Burns is a documentary filmmaker that gets it. Burns takes an extraordinary amount of energy to put all the pieces together, painstakingly marrying historical photos with indelible narration and interviews about a certain subject. His past work includes The Civil War, The War and Baseball. All of which were remarkable works of art.

If you are a photographer (or not) these documentaries put you right in the drivers seat. The riveting Dust Bowl images of Arthur Rothstein, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Walker Evans and others of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) documented the human struggle of drought and the Great Depression.

As the story unfolded, I was reminded why photojournalists do what they do. We got in to the business to document the world one slice at a time. Although we’ve seen the Dust Bowl images a thousand times (well, at least I have) I’m still haunted by the eyes of the people therein. However fleeting they can be, the photographs chronicle in real truth the struggles of man against nature (and man-made nature).

I was absolutely immersed in the story when an image popped up on the screen of a construction crew standing for a portrait on U.S. Route 64 that parallelly splits the Oklahama Panhandle. There was my dad, off to the right in clear view standing on a paving machine. It was a Works Project Administration (WPA) job. I fell out of bed, tears came to my eyes.

Now you see, my dad was born in 1905 and had me when he was 59. A few years ago, he passed away of natural causes at 102. He would often tell me stories of farming wheat (with a ton of expletives thrown in for good measure) with his dad in the Oklahoma Panhandle of Beaver County, where a fair chunk of Burns story is told. He was just four when he plowed his first field with a till and draft horses, later steam engines came along, then finally gas powered tractors. I could relate a hundred stories here. Suffice it to say that the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl took a lobe of my dad’s memory. After years of battling the elements and falling wheat prices, ” I only got 13 cents a bushell one year.” He decided he’d had enough and left the farm equipment in the field to pursue other avenues of making money. As thousands of others did.

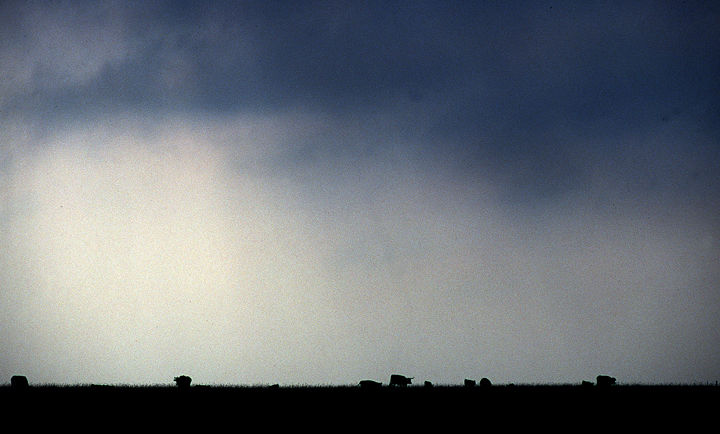

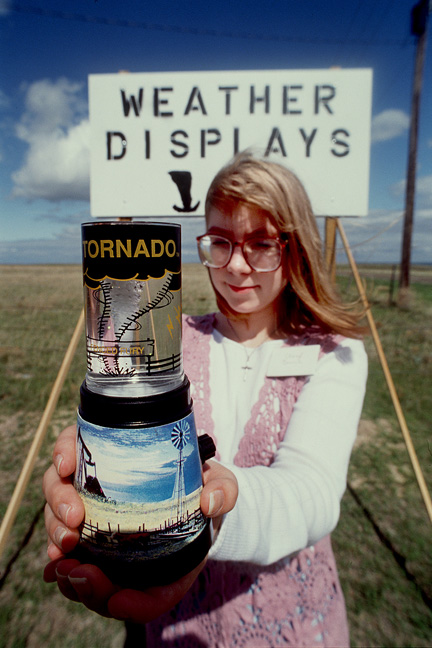

When I was younger, he would take me back there to meet relatives. I remember so much about Oklahoma and the Southern Plains. The thunderstorms, tornadoes, the undulating gentleness of the land. The way wheat waved under an evening sun, windmills creaking and pumping in the wind carved iconic memories that have shaped and molded who I am as a photographer, a husband and father; as a person. I romanticize about going back and spending a month in the Southern Plains, documenting the landscape. I’ve only touched the surface; photographically really not much at all.

Vicariously, I have dreams and memories to live on for now.

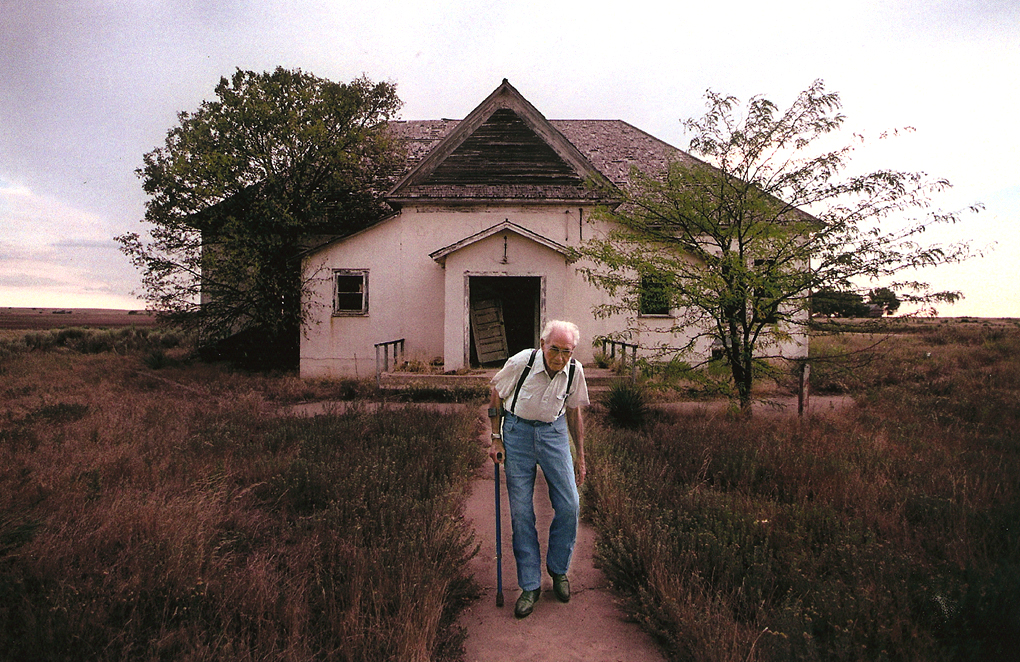

My dad, Harry Porter, then 95, walks from Sunrise School that he attended until the eighth grade in Beaver County Oklahoma. Kent Porter archives 2000.

-Kent Porter